In fact, the Pfizer doctor who organized the study told The Washington Post that antibiotics "would never be used like that in the United States. The usual treatment for meningitis in such urgent conditions would be intravenous antibiotics. To these critics, it was unethical to test an experimental drug orally in the midst of an epidemic. But critics such as Médecins Sans Frontières, the Nobel Prize– winning international medical relief organization, charge that this was exactly the sort of study that would not have been permitted in the United States. Those are the bare outlines of what happened. Pfizer then asked the FDA to approve Trovan for children with meningitis. After two weeks, an equal number had died, suggesting that the new drug worked as well as the old one.

Hoping to show that the drug, Trovan, was as effective for children in pill form as traditionally-used fast-acting intravenous antibiotics, Pfizer's doctors gave Trovan to 200 children.

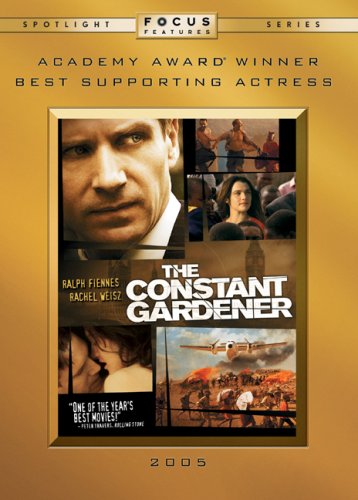

THE CONSTANT GARDENER MOVIE TRIAL

She goes on to discuss Pfizer's trial in Kano, then suffering from an epidemic of bacterial meningitis at the same time as Pfizer was seeking FDA approval for a new meningitis drug. "In fact, many of the practices that so horrified le Carré's heroine are fairly standard and generally well known and accepted." "The story is based on the premise that a pharmaceutical company would be so threatened by disclosures of its activities that it would have someone killed," wrote Angell. The parallel has been widely noted, most eloquently by former New England Journal of Medicine editor Marcia Angell, who reviewed the film in the New York Review of Books. Details of the clinical trial that prompted the Nigerian lawsuit against Pfizer are eerily similar to The Constant Gardener, a John le Carr_é_ novel-based 2005 film about one couple's fight against a transnational drug company's exploitation of poor Kenyans.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)